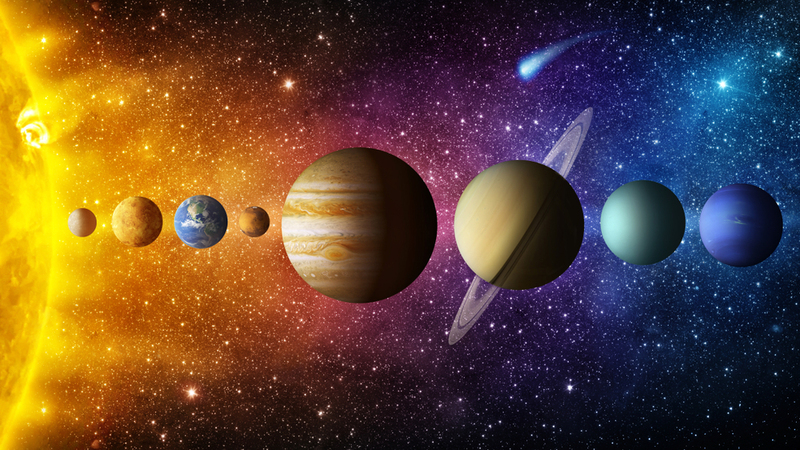

One of the most impressive planets in our solar system is Saturn. With the beautiful rings surrounding it, mankind has been looking to explore it for centuries. Take a second to learn a little about Saturn and then flex your astronomy muscles in front of your friends.

Before Uranus, Neptun, and other astronomical objects were discovered, Saturn was perceived as the furthest planet from Earth. Just like Uranus and Neptun, Saturn is a gas giant. As the term suggests, it is mostly made of gas and it is considerably larger than Earth. 95 times bigger, to be exact. Still, because it’s made of gas it is a lot less dense. In fact, Saturn’s density is lower than water’s. This means that if we had a ginormous space bathtub that could fit Saturn in it, the planet would float in it!

Discovering the rings

In 1610, Galileo Galilei studied Saturn and noticed something weird: Saturn seemed to have two astronomical objects orbiting it as it rotates. For two years, Galileo tracked the movement of those two objects until they finally disappeared. He saw them back again in 1616, this time looking like two little handles around the planet. In 1656, Denish scientist Christiaan Huygens solved the mystery. He came up with the idea of angled rings orbiting Saturn and that their angle in relation to the planet slowly changes all the time.

Saturn’s rings are very flat. How thin? About 180 thousand miles wide and less than a mile thick! Once every 15 years, the rings’ angle changes so they turn their profile to Earth. When that happens, we can’t see them at all. This is why Galileo couldn’t see them in 1612.

Solving mysteries

At first, Saturn’s rings were thought to be one single ring made of solid matter, but that sparked many arguments within the scientific community. Physicist James Clerk Maxwell is the one who figured it can’t be solid matter because that kind of ring would shatter from its planet’s gravity pulling on its inside. His theory was that the ring was made of numerous small objects that appear to be solid from a great distance. Good job Maxwell!

The scientist who discovered that there was more than one ring was Jacques Dominique Cassini. In 1675, he ran the Paris Planetarium and noticed thin black lines along the ring, dividing it into seven concentric rings orbiting Saturn.