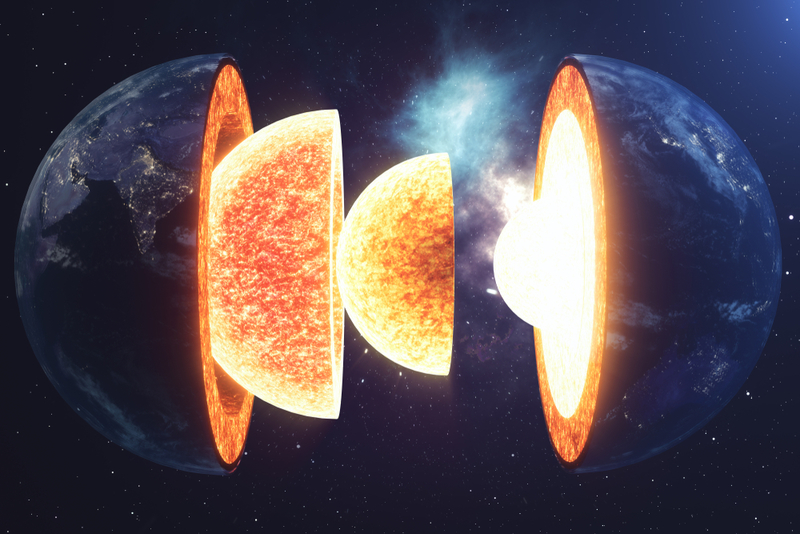

Understanding earthquakes requires a brief journey to the center of the Earth, where there’s a solid ball of iron along with other metals that can reach temperatures up to 10,800°F. We can’t even begin to imagine how extreme the heat from that inner core is. It emanates through its surrounding layers — first through the outer core, mostly made of liquid iron and nickel, and then on to the outer layer called the mantle. This heating process causes continuous movement in the cover, making the Earth’s crust above it move. The crust comprises a patchwork of individual giant rock slabs called tectonic plates. Sometimes when two plates are glissading against each other, the friction between their jagged edges temporarily gets stuck, which causes pressure to build until it can overcome the friction, and the plates finally go their separate ways. At this point, all the pent-up energy is released in ripples — or seismic waves — that shake the land sitting on the Earth’s crust.

Unfortunately, there’s no fancy apparatus that warns us whenever an earthquake is coming. But while scientists can’t predict precisely when or where we can expect an earthquake, they can occasionally forecast the probability that one will strike in a specific area, at an approximate time. For one, they know where the tectonic plates border each other, which is where earthquakes occur. They also know that massive earthquakes are sometimes preceded by tiny quakes called foreshocks. When smaller quakes near a plate boundary coincide with other geological changes, it can indicate that a bigger earthquake is coming. For instance, in February 1975, the Chinese city of Haicheng experienced possible foreshocks after months of shifts in land elevation and water levels. Hence, city officials ordered their residents to evacuate immediately. The very next day, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake hit the region. Though there were 2000 casualties, it did spare 150,000 who could have been killed or injured if nobody had fled.

Because so much of the surface of our planet is water, many earthquakes don’t even reach land, but that doesn’t mean they don’t affect those who live on it. When plates constantly shift on the ocean floor, the energy displaces the water above them, causing it to rise dramatically. Then, gravity pulls that water back down, making all the surrounding water form a tsunami. So indirectly, earthquakes can alter the landscape by causing tsunamis. On July 9, 1958, a 7.8-magnitude quake hit Lituya Bay in Alaska, causing a rockslide on a bordering cliff; the force created the largest tsunami in the form of a 1720-foot wave.